Following Dylan’s Writing Routine: Part 1

Katie, the Dylan Thomas Centre’s resident writer, finds a particularly dedicated way in which to research Dylan’s writing routine.

‘We are both slaves to habit’ wrote Dylan to Pamela Hansford Johnson in early January 1934. As it was, Dylan’s writing habits and routine in 1934 bore a marked similarity to the routine he adopted over subsequent years. Indeed, the years when he was most prolific seemed to be those when he could most adhere to that routine. I write in my spare time, not poetry but plays, monologues and short stories. Normally I write at random hours in the evening, or on weekends when I’m avoiding doing household chores. But what could I achieve with a more rigorous schedule? More specifically, how would I fare if I conformed to Dylan’s regime? I decided to take a week off work and find out…

The routine

In a letter to Pamela Johnson in early January 1934, Dylan writes about his daily schedule. Caitlin, in Caitlin: Life with Dylan Thomas describes how Dylan worked in New Quay and Laugharne. The routine I committed myself to was an amalgamation of these two descriptions. It was as follows: 10-12.30 reading, 12.30-1.00 lunch, 1.00- 6.00 writing. When he was younger, Dylan would occasionally continue writing in the evenings and so I made this an optional extra.

The mornings

‘At half past nine there is a slight stirring in the Thomas body’ (Letter to Pamela Hansford Johnson, January 1934)

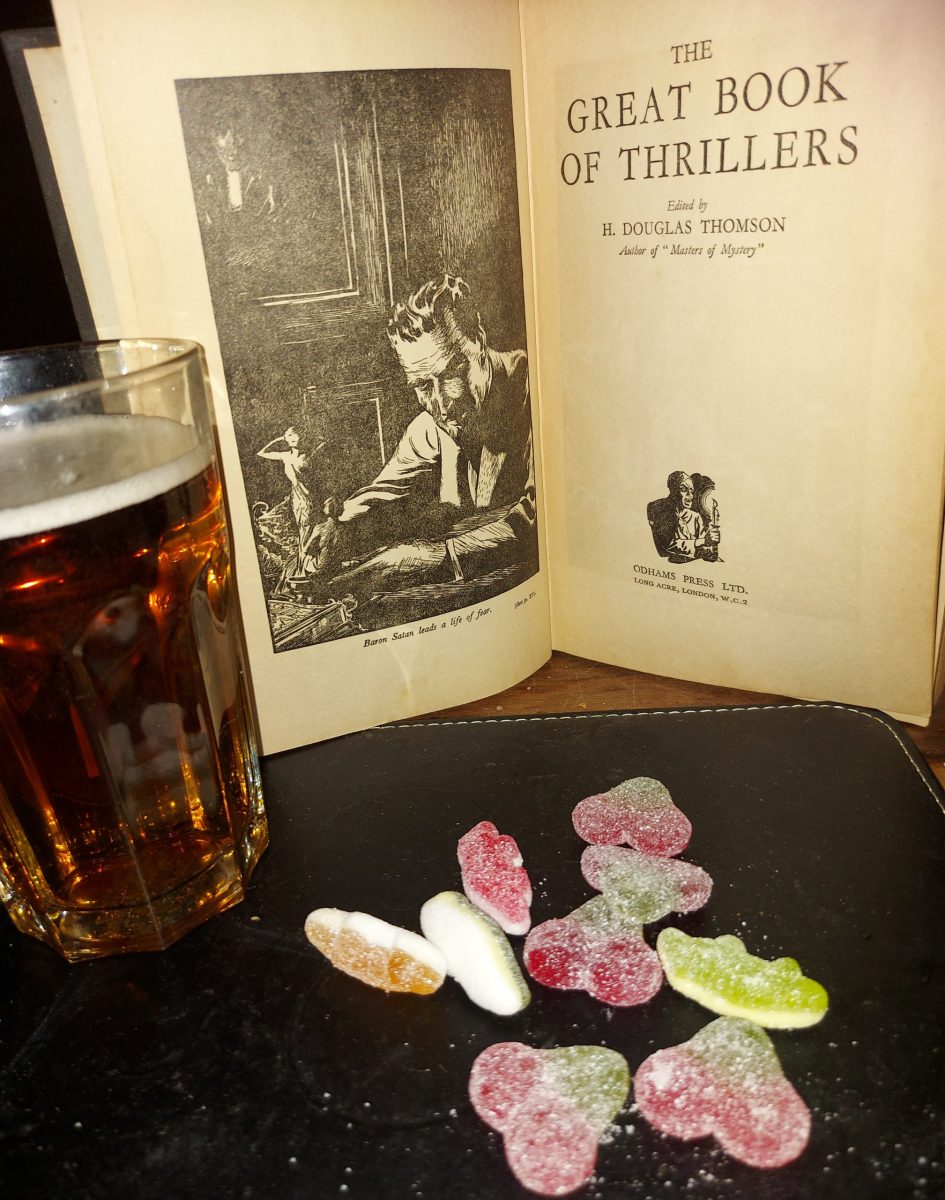

Dylan was a voracious reader. In his letter to Pamela Hansford Johnson, he explained that he would start the day by reading the morning paper and then proceed to read ‘anything that is near’, poetry, prose and plays. When in Laugharne he would read and then go and visit his parents, completing The Times crossword with his father. In short, reading was an intrinsic part of the working day. Dylan found books inspirational. In Dylan Remembered Volume One Bert Trick recalled Dylan reading a book of Italian medieval legends. He said the subsequent poem ‘When, like a running grave’ was inspired by one of the tales therein. In Dylan Remembered Volume Two, Vernon Watkins recollects that Dylan ‘found a germ of a poem in an extremely bad thriller’.In a letter to Henry Treece in March 1938 Dylan stated that ‘a good number’ of his images came from ‘cinema & the gramophone and the newspaper’.

Following Dylan’s regime, but without the luxury of being served breakfast in bed, I made sure I was armed with a book by ten o’clock in the morning. Knowing Dylan had a penchant for thrillers and crime books, I devoted my mornings to reading these and reading the latest news online.

At about noon Dylan would go to the pub (The Uplands Hotel in Swansea and Brown’s in Laugharne) where he would have a pint or two and listen to the latest gossip. I didn’t partake in a pint but I would, at this point, catch up with any messages from friends and have a quick scroll through my social media.

Dylan would return home for lunch, over which he would continue to read. Caitlin observed that he would eat in a separate room from her and the children and read ‘novels, poems, comics, even the back of sauce bottles’. I, too, read through lunch.

In 1951 a student, writing a thesis on Dylan’s poetry, wrote to Dylan asking him questions about his work. Dylan’s answers were later published in Texas Quarterly, Winter 1961, under the title of ‘Dylan Thomas’s Poetic Manifesto’. In it, Dylan states: ‘My first, and greatest, liberty was that of being able to read everything and anything I cared to’. For me, setting aside time to read in the mornings was quite revelatory. All too often I have found that I guilt myself into not reading as much, feeling that I should be devoting my free time to writing instead. Reading almost feels like procrastination. Although, at times, it certainly can be (Caitlin said how she used to remove Dylan’s detective novels from the Writing Shed so that Dylan wouldn’t be distracted by them when he was writing) it also seems to be a fundamental part of the writing process. Reading as extensively as Dylan did helped him to distinguish between good and bad writing, helped him to aspire to the former and avoid the pitfalls of the latter. Since completing my last writing project I had found myself, quite frankly, void of ideas for something new. However, after a week of reading every morning, I felt far more in touch with the creative process and my mind was ticking through ideas for a monologue, a short story and a one act play. The question was, how would these ideas translate into writing? I would find out when I followed Dylan’s regime for writing in the afternoon.

Katie Bowman, Dylan Thomas Centre

This post is also available in: Welsh