Life at Blashford | October 1937- April 1938

Linda’s latest blog focuses on Dylan and Caitlin’s stay in Blashford, Hampshire, shortly after their marriage.

Before Dylan Thomas married Caitlin Macnamara in July 1937, neither had met their prospective parents-in-law. On discovering their wedding plans, Dylan’s brother-in-law, Haydn Taylor, warned Caitlin’s mother against allowing her youngest daughter to wed a penniless young bohemian poet with a reputation for irresponsible behaviour.

Dylan’s broad-minded mother-in-law, Yvonne, (who herself had eloped with Francis, an impecunious self-styled poet), did not oppose the marriage. However, Dylan frequently felt that she was disappointed with Caitlin’s choice.

Following their honeymoon in Cornwall, Dylan introduced his new wife to his parents in Swansea, after which the newlyweds settled for six months at Caitlin’s family home in Blashford, on the edge of the New Forest in Hampshire. New Inn House (demolished in the 1970s to make way for a nature reserve) was a rambling former pub with several acres of land. Caitlin’s parents had divorced when she was very young, although the family had already been brushed by the ‘allurements of bohemia’ (as Dylan’s biographer Paul Ferris put it), through her father’s long friendship with the poet Augustus John, who lived nearby.

The couple’s respective upbringings had been very different; while Dylan grew up within the stultifying parameters of respectability in suburban Swansea, mollycoddled to the extreme by his mother, Caitlin, her brother John and elder sisters Nicolette and Brigit’s unstructured upbringing was short on discipline or guiding principles. Dylan’s mother, Florence, would have been shocked by the lax housekeeping standards: piles of bills and laundry which remained where they accumulated, and stacks of books, magazines and papers lying around, including comics and literary reviews.

However, Nicolette, in her autobiographical account ‘Two Flamboyant Fathers’, says her mother ‘kept a sanctuary of tidiness in her special sitting room’. Out of bounds to children and family pets, it was lined with fiction, where Yvonne would disappear to read, leaving the children to their own devices. Perhaps her refined upbringing did not prepare her for the hands-on parenting that a pervasive lack of money necessitated.

Dylan thought Blashford a ‘lovely place’ and certainly appreciated the unstructured, ‘laissez-faire’ (yet cultivated) way of life. He told Swansea friend and poet, Vernon Watkins, that the house was stacked with prose books and he’d read (amongst others) ‘two dozen thrillers, the whole of Jane Austen, a new Wodehouse, some old Powys…There are only about 2000 books left in the house’.

Nicolette recalls Dylan inventing parlour games, schoolboyish ‘tortures’ which involved imagining (and enacting) eating a honey and mouse sandwich or sitting ‘naked in a bath of white mice’. Unsurprisingly, he also had an expert knowledge of comics and ‘discussed with relish’ the adventures of the cartoon character Billy Bunter.

When not entertaining the household, Dylan appreciated the extensive grounds, which were peaceful and conducive to the artistic temperament. As a child, Caitlin adopted a disused wooden hencoop as a den, where she and Brigit would play invented games. Now it was converted into a makeshift summerhouse; sheltered by its rose-covered corrugated-iron roof, in which on fine autumn days Nicolette recalls Dylan reading poetry aloud.

Dylan became morose if he was not writing, so he was allowed to use the grandest room at New Inn. A former wood shed, it had been converted as a place for special occasions and looked out on the garden at the rear. In winter, he wrote wearing multiple layers of clothes in an attempt to keep out the biting cold. Nicolette remembers Dylan writing some of his poems in there, where he: ‘scattered the room with scraps of paper that were chucked into the waste-paper basket at the end of the morning. These were discarded lines, in his miniscule, neat handwriting’. In November 1937 Dylan sent Vernon his two newest poems written there, ‘I make this in a warring absence’, and ‘The Spire Cranes’. New light was shed on his writing at this time by the discovery, in 2014, of his Notebook from this time containing drafts of his poems.

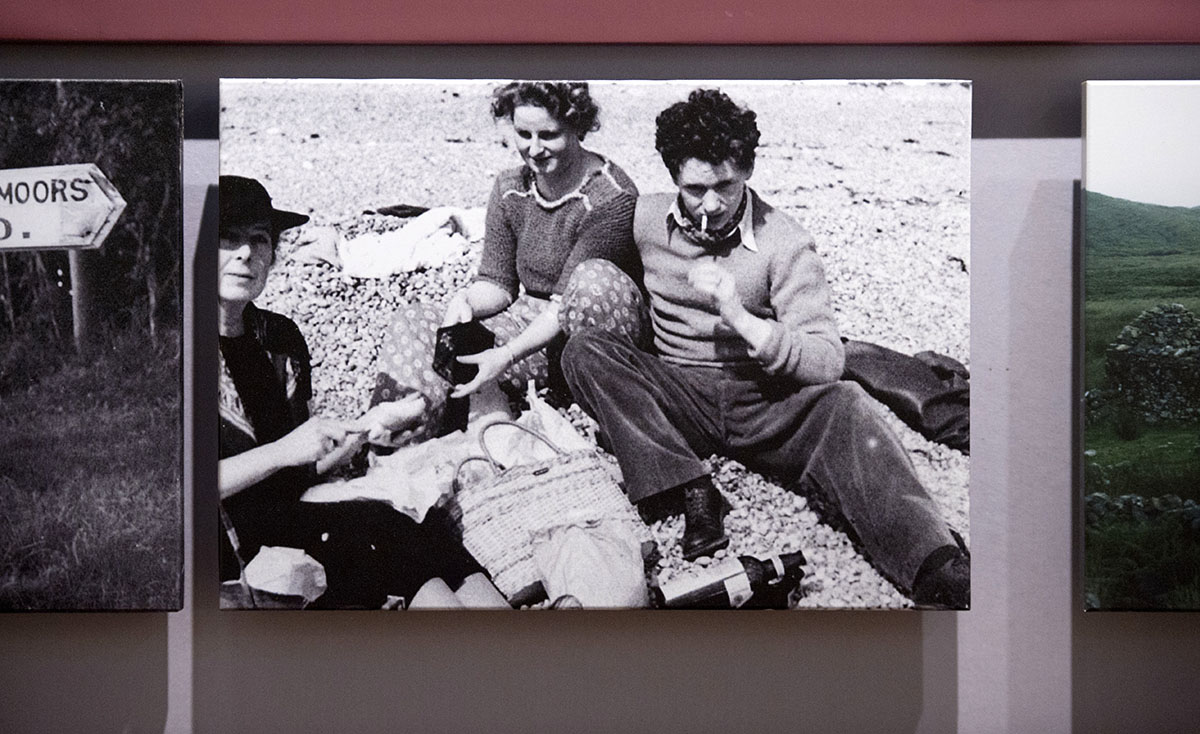

The young poet soon formed a routine; just before noon, he concluded his work and he and Caitlin went into nearby Ringwood for a beer at the Royal Oak pub (now a restaurant). They then returned home loaded with fizzy drinks and numerous types of sweets, including liquorice allsorts and dolly mixtures, which they ate in bed while reading aloud to each other, returning to the pub in the evening with Brigit and occasionally John.

On fine days the couple often went on cycling expeditions into the New Forest and trips to local beauty spots, including the striking Dorset coastal landmark, Durdle Door. One senses it was a relatively indulgent and carefree six months, unfettered by events that would later sour their relationship. It is an interesting glimpse into a time when Dylan was consolidating lifelong working practices, where he had the freedom to be himself without parental concerns and interference, even if he sometimes missed the maternal indulgences of home.

Linda Evans, Dylan Thomas Centre

This post is also available in: Welsh